Three Dogs

plus a few more

In “Honored Guest” by Joy Williams, a dying woman observes, “There were only so many dogs in a person’s life and this was the last one in hers.” I have wondered about my last dog, the one who will outlive me. I’m preemptively grateful to him for enduring my death. Notably, Lenore of “Honored Guest” feels no tenderness toward her last dog; she resents him for stealing her slipper and growling. Before she dies, she rehomes him, reclaims her slipper. The story isn’t really about Lenore’s dog. It’s about her inevitable abandonment of her teenage daughter. The dog is a witness, until he isn’t.

Inconveniently Large Mutt is my preferred breed of dog, though I’ve fantasized about growing elderly and indulging in a long-haired Dachshund. A dog I can scoop into my arms, carry onto a plane. I feel better when I’m touching an animal. If my only relationships were with humans, I’m certain I would go insane.

Last weekend, Dan and I saw Kelly Reichardt’s 2006 film Old Joy, in which two friends—one of whom is Will Oldham/Bonnie “Prince” Billy—go camping with a dog. The dog is Lucy, who was Reichardt’s own dog, and who also starred in Wendy and Lucy (2008), which I am presently too pregnant to rewatch. I love these movies for including a dog who is not a perfectly trained Hollywood purebred, but a lithe little pit bull mix pleased to drag a stick through the woods beside boys she doesn’t know are acting. She’s not performing, not panting in anxious servitude. Lucy doesn’t appear to expect a treat for balancing on a fallen log to cross a stream. Or as she sleeps on a couch discarded in the brush. When the trip is over, she hops into the back of a Volvo station wagon only after Will Oldham calls her name. Her real name.

Old Joy made me unspeakably sad for a few reasons. One is that I lived in Portland in 2006, and everyone I knew drove an ancient Volvo, and everyone I knew was a beloved childhood friend of precarious mental health. Driving vaguely south through the forest in search of hot springs, giving up and camping in a junkyard, is approximately how I spent my adolescence. It makes me sad to think of those same forests on fire, those Volvos in pieces, the boys to whom I’ll never speak again. But mainly, I got sad thinking about Lucy. How she was a part of Reichardt’s life and work until she wasn’t. Dogs don’t live as long as people, but if you are the kind of person who must always have a dog, your dogs measure your life with theirs.

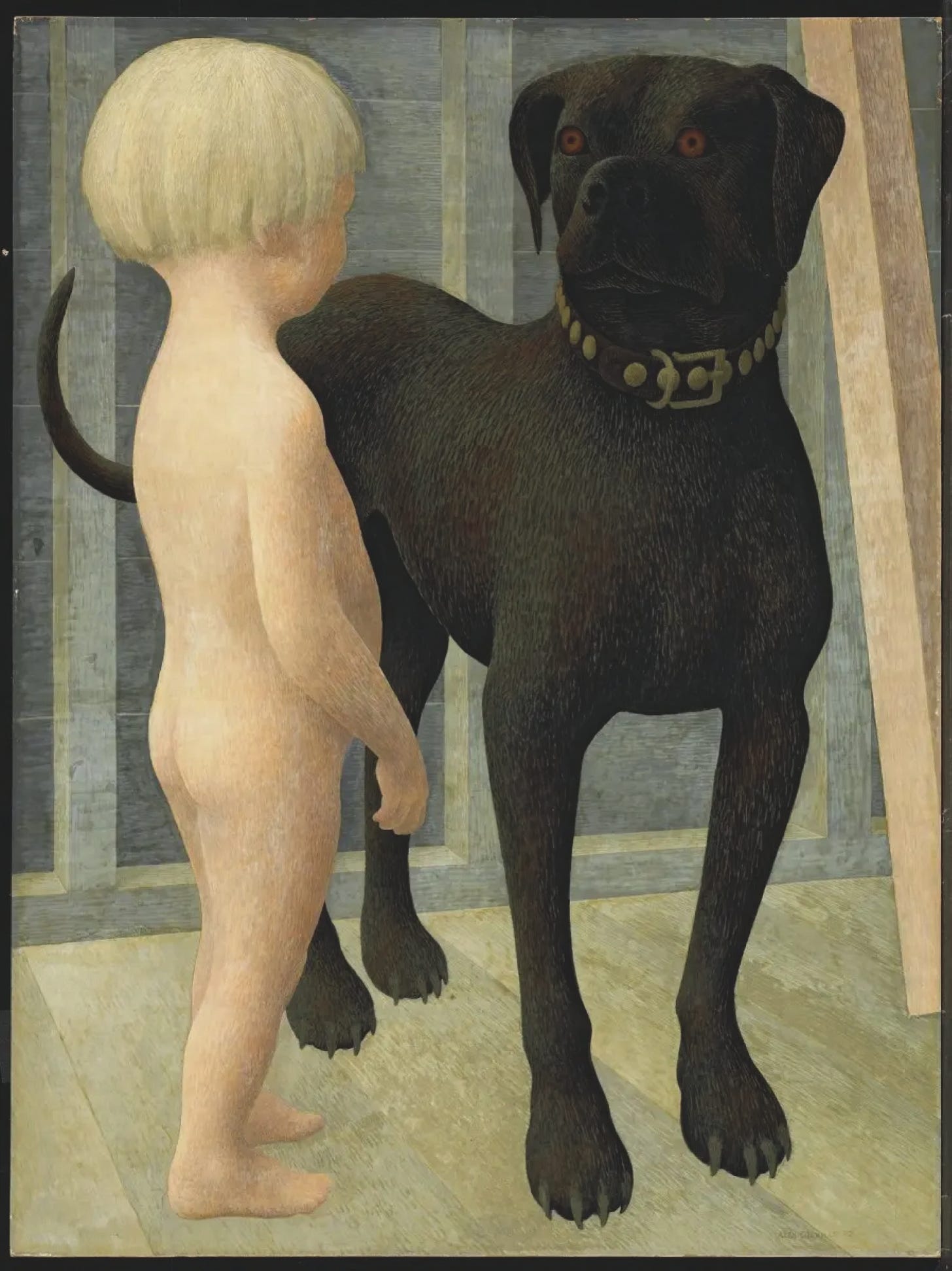

Hank was half German Shepherd, half Australian Cattle Dog. He saw me through age twenty-one, drunk in a Toronto taxi, to age thirty-four, a mom in Connecticut. A few years into Hank’s life, I went to an Alex Colville exhibit at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Like Williams and Reichardt, Colville included dogs in his work. Not dogs as accessories or symbols, but dogs are they really are: running loose, chewing bones, looking nervous near a cat, peering into an oven, solemnly riding in the back of a car. One of my favorite Colville paintings is Child and Dog, 1952, in which a naked toddler and an orange-eyed Rottweiler stand staring at each other. Colville’s paintings famously captured moments of stillness, tension, threat. He painted storms brewing, guns on tables. His paintings are works of narrative. What just happened? What will happen next?

I am more intolerant than I should be of people who dislike dogs. I’m suspicious of anyone who automatically trusts a human over an animal, or who disregards animals as dangerous, soulless, unpredictable, or burdensome. Because I have spent my life among them, I’ve been bitten by dogs, decked by horses, scratched by cats. I’m protective of my kid around other people’s pets, nervous for the day he’s thrown from his favorite mare at the barn. I also know that animals are individuals. We earn their trust and they earn ours. A dog’s temperament will shift and fluctuate over the course of her life, but she can still be deeply known. Of his work, Colville said, “To me the presence of animals seems absolutely necessary. I feel that without animals everything is incomplete.” The child in Child and Dog is his own daughter, the Rottweiler a member of their family.

I am thirty-seven weeks pregnant and have been thinking about the impossibility of making children be who you want them to be. It’s nice to imagine we don’t want our children to be anything in particular. In truth, your children are people with whom you spend a shitload of time; shared interests can make the time more enjoyable. My eight-year-old is, I suspect, even less malleable than the average kid. His dad, who has that permanent athleticism with which some men are weirdly blessed, tried very hard to get Wes to throw a ball, or hit a ball, or be able to identify varieties of ball. Still, driving past a middle school lacrosse practice, Wes will confidently say, “A baseball game!” then resume singing the bridge to “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived.”

I remember Dan’s efforts to make Wes sporty when I wonder if I’ve forced my love of dogs on our child. For sure, from the time he was born, I gave Wes ample opportunity to be comfortable around animals, but I think his comfort is largely ingrained, inherited. Two summers ago, while we were visiting my parents after a semester at Deep Springs, Wes attended a week of goat camp in Washougal, Washington. Goat camp was hosted by a homeschooling hippie couple on their sloped, overgrown property in the foothills of the Cascades. The kids bottle-fed the goats, hiked with the goats, ate sack lunches in proximity of the goats. Wes loved the goats but not as much as he loved the farm’s livestock guardians, two enormous, loud, ungroomed Great Pyrenees. “Can we get a dog like that?” he asked me.

The answer was obviously no. At the time, Hank was still alive and we lived most of the year in a two-bedroom apartment in New Haven. Great Pyrs weigh over a hundred pounds and are bred to pace the perimeter of your property barking at any sound a coyote could conceivably have made. Great Pyrs are also routinely abandoned in southern states. Ranchers fail to sterilize their working dogs and resort to dumping the unwanted puppies. When I noncommittally telephoned a woman who runs a rescue in Lockhart, Texas, she was desperate to transport a particular six-month-old male anywhere in the country. She texted me Sammy’s picture and the answer was, as it had always been, yes.

The first thing Sammy does in the morning is check on each of his family members. I wake to a wet nose and white eyelashes making sure I made it through the night. If Sammy lives as long as Hank, he’ll see us through the birth of our daughter, Wes’s graduation from high school, our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. If we’re lucky, he’ll witness so many things we don’t yet know will happen.